Biography of Rice

Biography of Rice is an installation exploring the hybridity of cultures found in the immigrant, the misrepresentation of cultures, and the longing for cultural history and identification through the creation of an interactive sculpture alongside projections on rice paper molds. The interactive CatDragon sculpture is part Maneki-neko, or the Beckoning Cat, and part Lion dancer. It is part electronic, part mechanical, part divinity, and part domestic. It is an inhabitable sculpture, used as a proxy for my body and representation of a female immigrant experience. Women have historically been connected with the household or the home, but what is home to someone who is displaced— who has both no-place and a collection of various places? I am interested in creating a place where the hybrid can be harmonious with its environment, and the relationship between viewer, audience, performer, and participant are interlaced and interchangeable.

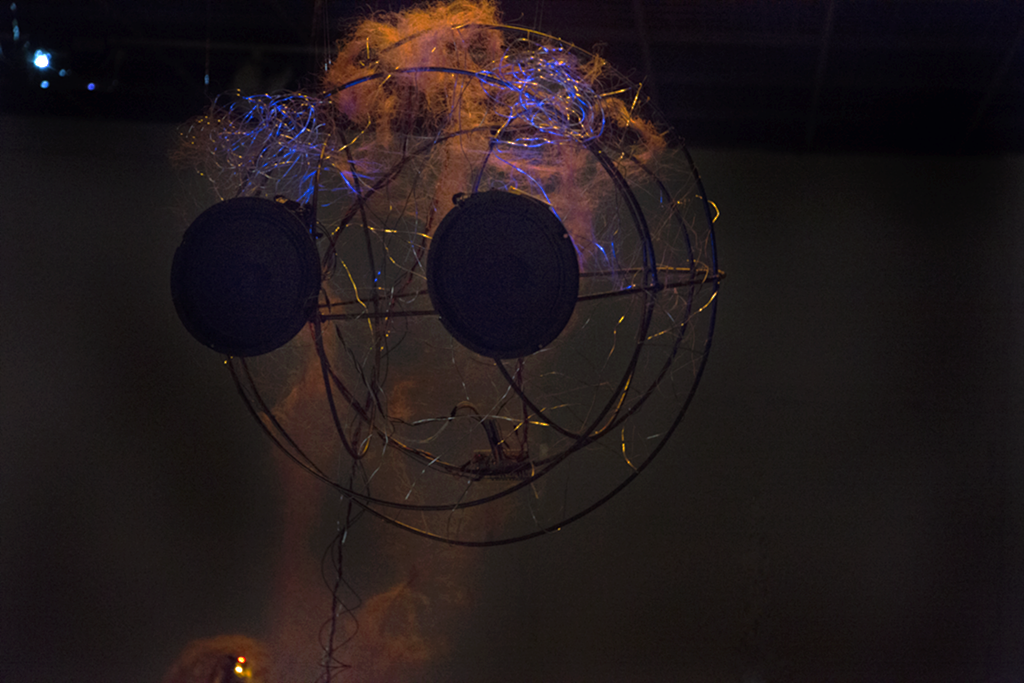

The interactive, inhabitable CatDragon is housed near the center of the exhibition.Why cats? Cats appear as symbols of feminine identity through various cultural histories. It is perhaps most popularly cited as an aspect of ancient Egyptian culture, where domestic cats became the symbol for grace and poise. Cats were often depicted under a woman’s chair representing fertility and sexuality. In the European Middle Ages, the cat’s aloofness, independence, and nocturnal behavior led them to be associated with paganism and witchcraft, and the church led a massive inquisition that slaughtered them to near-extinction in 1400. In Ypres, Belgium, there is a annual parade called Kattenstoet, or the Festival of the Cats, that commemorates the historical throwing and killing of cats because of their association with witchcraft. These metaphors continue to thrive today in numerous expressions in Western culture: a predatory woman is a “cougar,” nasty woman are referred as “catty” and can get into “cat fights,” an old woman without a life partner is seen as a “cat lady” and female sexual organs and men who are believed to be weak are referred as “pussies” and “kitties.” There is still a culture of fear and mystery that surrounds both cats and women, which is why I am referencing cats as the symbol of female identity.

Focusing on the legend of Maneki-neko and the divinity of cats, I am attempting to personify a Southeast Asian immigrant body. The Maneki-neko, or Beckoning cat, first appeared during the Eno period in Japan. There are many origin folktales of the Maneki-neko, with the most popular being the Goutokuji temple story and the beheaded cat story. In the beheaded cat story, a young woman has a beloved cat. One day, a swordsman friend visits her, and her cat becomes frantic. The swordsman believes the cat is evil and is attacking the young woman, and beheads the cat. The cat’s head flies through the air and bites into a venomous snake, who was waiting to strike the woman. The Goutokuji temple story tells the origin of its name, the Cat Temple, and cat shrines. In this story, a monk cared for a cat like a child, and one day five or six samurai came to his temple for some rest. The samurai told the monk they noticed a cat beckoning to them on the road, and, intrigued, they came across his temple. Suddenly, the sky darkened and it began to rain. Waiting for the rain to stop, the Monk preached Sanzei-inga-no-hou (past, present, future reasoning sermons). The samurai were delighted with the preachings and decided to convert to the temple, declaring it Buddha’s Will. Thus, the Goutokuji temple became prosperous, and the Maneki-neko became a symbol of household serenity and prosperity. Today, one can find the Maneki-neko in most all Southeast Asian establishments, especially Chinese restaurants, in the United States. They have become so present in Chinese restaurants that they are often placed with other Chinese shrines and are mistakenly identified as Chinese in origin. I am interested in how displacement yields power to the malleability of the Beckoning Cat to cross between cultures; and how displacements bring together collective cultures that aren’t found in the home countries.

I have created a mechanical sculpture that is an amalgamation of the Maneki-neko and the Southern Chinese Lion Dancer in an attempt to abstract into form the notion of hybridity from culture globalization and collective identification. There are many versions of the Lion Dance, including versions from Vietnam, Korea, Japan, Tibet, and Indonesia. However, the most widely spread version of the Lion Dance is the Southern Chinese Lion Dance, which was spread by Chinese diaspora communities that were historically from southern China, especially the Guangdong province. The Lion Dance is usually performed during communal celebrations, like the Lunar New Year, with two people completely encapsulated in the Lion. In Biography of Rice, visitors also have to encapsulate themselves inside the CatDragon, where they find the controls to change the audio coming out of the CatDragon’s eyes and to make the sculpture dance.

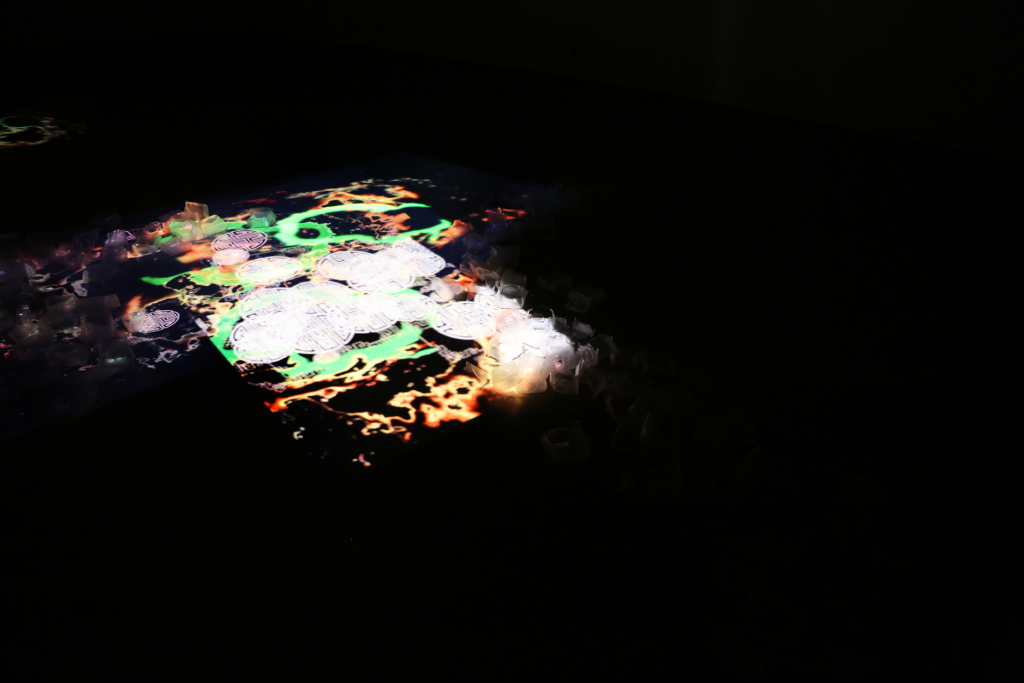

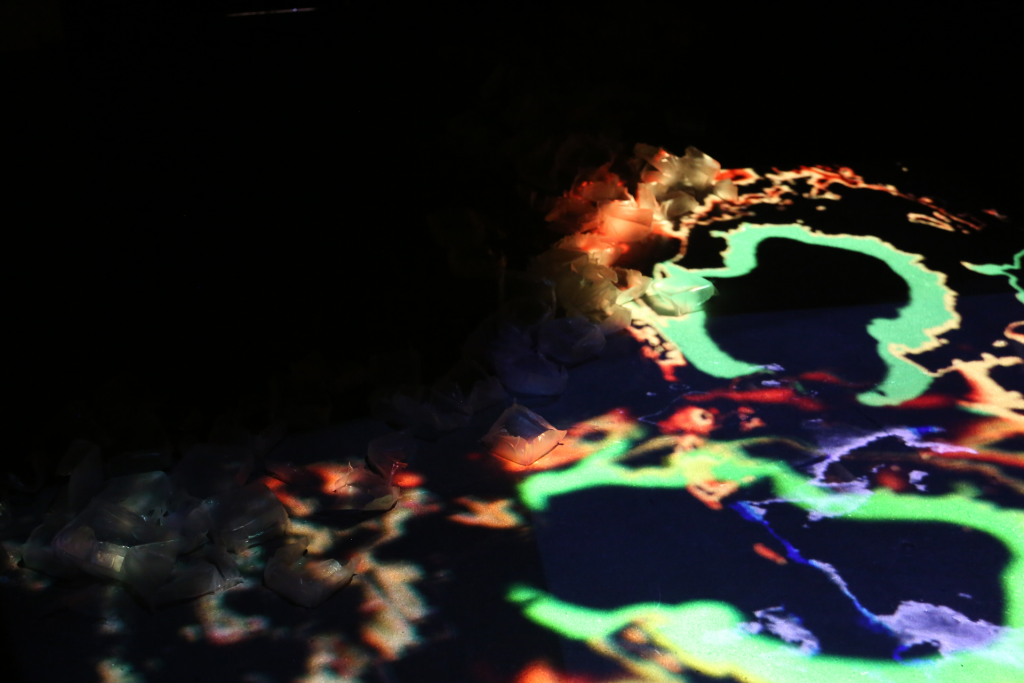

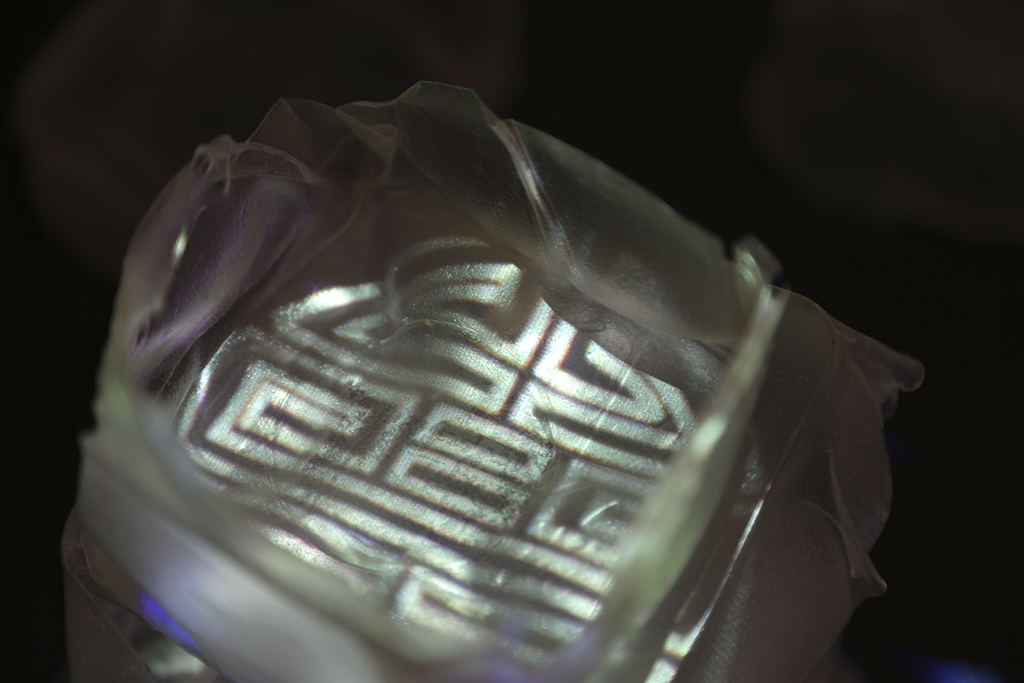

Surrounding the CatDragon are geometric molds made from rice paper, around four-by-three inches wide and two inches deep. They are molds of a specific mooncake tin that I have kept since childhood to store small items like my button collection and sewing supplies. There are about 400 replications of the negative space of the mooncake tin. Mooncake is a traditional Chinese bakery item that’s eaten during the Mid-Autumn festival, which is August 15th on the lunar calendar. Mooncake consists of a pastry skin enveloping a sweet interior (usually a lotus seed paste) and may have one or two salted egg yolks, which symbolizes the full moon. There is usually a character for “longevity” or “harmony” imprinted on top of the mooncake. Eating mooncake is supposed to be a metaphoric sacrifice to the moon for Autumn. Mid-Autumn festival is also one of three traditional Chinese holidays that my family still celebrates, alongside the Lunar New Year. I surrounded the CatDragon with the rice paper molds so that it forms a circular pathway from the door to the CatDragon. It was my intention for viewers to navigate their way along the pathway, to circle around the CatDragon, and end in a dead-end with the CatDragon itself. Although I created a path for the visitors, I also invited them to make their own way towards the CatDragon: I scattered the broken pieces of the rice paper molds along pathway as “evidence” that some visitors had already broken away from the path; and when someone did break from the path, they would most likely hear the crunch of one of the fragile rice paper molds breaking.

Projected onto the floor of the installation, along the pathway of the rice paper molds, are animations exploring the character for “longevity” or “harmony.” As mentioned previously, the character for “longevity” or “harmony” is usually imprinted on the top crust of a mooncake. However, these are highly stylized, almost unreadable characters, with the character itself abstracted into a circular form inside a stylized square. Not only are these symbols found on mooncakes, they are also found on red envelopes for the Lunar New Year, and in Chinese and Western “oriental” architecture and furniture. I believe these symbols to be an automatic signifer of “Chinese-ness,” I began my research to find out more about these symbols by searching “Chinese design,” on Google Images. The symbol I used in my animations is one of the first images that I found online. It was a copyrighted vector, stock image file. I was interested in how an online database had more rights and claims to the symbol than myself, whose heritage and culture are intertwined with the symbol. I researched that specific symbol, and found that it was in fact meaningless: it was supposed to be the character for “longevity,” however it had extra strokes that aren’t in “longevity” that were included for purely aesthetic reasons. I decided to pair this clearly Eastern-looking symbol in an abstract color animation, and projected this animation multiple times on the floor. The animations followed the pathway of the rice paper molds, and many of the molds reflected and refracted the light from the projections; this illustrated the metaphor of ghosts and lost in the installation. Biography of Rice is a personal piece exploring my journey to locate and connect to my roots or culture; however, in our globalized virtual present, is this journey perpetually impossible? Can the hybrid find harmony with its environment, or does it become a dystopian ruin, like my installation?

/// interactive installation

/// 6 channel animation

/// 2 mono speakers

/// ardunio

/// c++